Figure 1: Nepal-China border at Rasuwagadhi, Rasuwa District, Nepal; Nepalese oil tanker travelling empty to China for import purposes.

In the first three months of the fiscal year 2025/26, Nepal’s imports amounted to NPR 468 billion, while the total sum of Nepalese exports reached NPR 72.8 billion. With this, the Nepalese Customs Department has reported a gap of approximately NPR 395.3 billion.

This gap of NPR 395.3 billion is Nepal’s Trade Deficit, approximately. 3 billion $USD or 5% of our entire GDP. This gap primarily consists of the imports from our two big neighbors, India and China. Trade with India accounted for a deficit of NPR 199.7 billion, while with China, the gap was of NPR 104.70 billion.

Before diving any deeper, let us understand what a Trade Deficit really means.

What is Trade Deficit and How Does it Happen?

In Economics, a Trade Deficit occurs when a country buys more goods from other nations than it sells to them. i.e, the total value of imports is greater than the value of exports during a specific period in that country (The Economic Times). In Nepal’s case, this has been very common.

What do we import?

Our imports can be classified into three main groups: Primary Goods, Secondary Goods, and Final Products.

- Primary Goods: Our Energy Addiction

Primary Goods are raw, unprocessed, or less processed materials that are generated or extracted directly from the earth’s natural resources. These goods are used as fundamental production materials, which are then used to produce secondary or final products.

Import of Primary goods, specifically Mineral Fuels, holds the single largest drain on our foreign exchange. In the past three months, petrol worth Rs 16 billion 788 million, diesel worth Rs 20 billion 694 million, and 500 thousand, and LPG worth Rs 13 billion 981 million and 900 thousand were imported (The Himalayan Times). Nepal lacks oil and gas reserves, forcing us to become dependent on imports and perpetually pay international prices for them.

Figure 2: Nepalese oil imports being stored in a Nepal Oil Corporation site through imports from India Border.

- Secondary Goods: Our Factory Inputs

Secondary goods are materials or products that have undergone a certain level of processing. They are generally semi-finished. This includes steel billets (rods), crude vegetable oils, bulk plastic granules, and paper. Our demand for steel, iron, and metal products is linked with ongoing large-scale projects like hydropower and highways. Similarly, many other goods like plastic granules are mass imported for the packaging of Nepal-made food items and other products.

- Final Goods: Ultimate Demands

Final products fully undergo processing and are ready for immediate use. High-end products like cars, mobile phones, machinery and equipment, packaged foods, etc., are examples of final goods. These goods also have a greater capital value in the goods market than any other type of goods. Nepal imports a large amount of final products, especially automobiles and technology.

The Price of an NPR 400 Billion Deficit

The Nepalese economy is based on imports. The majority of the goods we use or consume are generally imported from our big neighbors, China and India. To buy goods from foreign countries, Nepal exchanges its NRP for the other currency. By exchanging our NPR, we increase the value of other currencies like the Chinese Yuan, $ US dollar, or the INR. At the same time, the demand for NPR remains low due to low exports. Additionally, due to large imports, there is an excess supply of NPR in the forex market.

Figure 3: Forex market example of the NPR, and how trade dynamics affect the value of a currency.

The excess supply shifts the supply of NPR from S1 to S2, where S1 is the initial supply of NPR and S2 is the final supply of NPR in the forex market after high imports. This puts downward pressure on the NPR, meaning that in the free forex market, the value of the NPR would automatically depreciate.

When Nepal runs large trade deficits, the Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) has to maintain the value of our currency by using foreign reserves. Foreign exchange reserves are foreign assets owned by a country’s central bank in the form of foreign currencies, bonds, and other securities (Investopedia).

However, the Nepalese Rupee (NPR) is pegged to the Indian Rupee (INR) at a fixed rate of 1.60:1. This means that the value of NPR is constant, and only changes when the direct value of INR changes. Through the pegged currency system, Nepal plays a safe game where even when the trade deficits become larger, the value of our currency doesn’t depreciate. But this also comes with another additional cost: to maintain this pegged rate of NPR 1 = INR 1.60, the Rastra Bank constantly needs to intervene in the forex market. The NRB uses its foreign reserves to buy NPR when there is a low demand for NPR in the market, artificially creating a demand, shifting the demand curve from D2 to D1, thereby maintaining a stable currency value.

We have a history of consistently having higher imports, but there are consequences to importing six times our exports. Nepal’s current import dependency weakens our trade position in the global trade market, while forcing the NRB to spend its reserves heavily and maintain the fixed rate of NPR to INR.

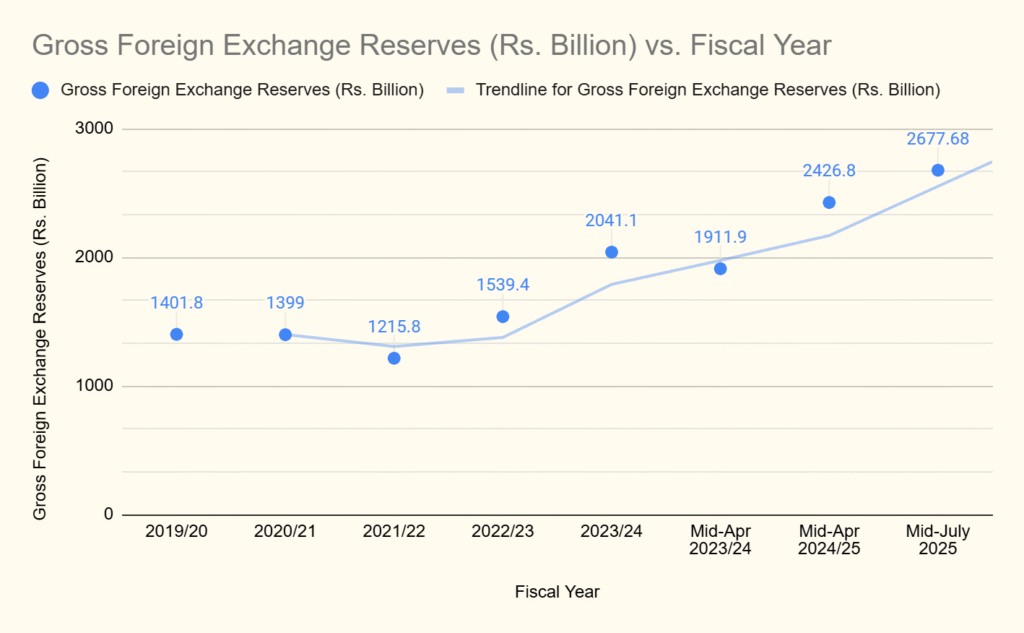

But here’s an interesting fact: Nepal Rastra Bank held the highest foreign exchange reserves in July 2025, the same quarter where our trade deficit soared NPR 400 billion.

Figure 4: Gross Foreign Exchange Reserves (Rs. Billion) against Fiscal Year, representing the massive exponential growth in the reserves since 2020.

In July of 2025, Nepal Rastra Bank reported that it currently holds a foreign reserve of NPR 2,677.68 billion. In US dollar terms, such reserves remained at 20.03 billion (MyRepublica)

You may be wondering about this contradiction. Every economist or economic researcher says that importing more puts a downward strain on the foreign exchange reserves, especially when imports are larger than exports. This is true from a logical point of view, and in Nepal’s case, our problem is rooted deeper than you think.

We import everything, from primary goods to final goods. Nepal affords this by exporting the blood and sweat of its citizens.

Figure 5: Nepalese youths overcrowding the International Terminal at TIA, in dreams of working abroad.

Nepal educates, raises, and exports its citizens to foreign countries as migrant workers. The Nepalese migrants work and earn money to send back to their families residing in Nepal. The International Labour Organization reported that the number of Nepalese workers going abroad increased by 102% between 2019 and 2023, one of the highest rates in Asia.

In 2023 alone, the remittances sent by migrant Nepalese workers accounted for over 26% of the entire GDP of the nation (ILO). This form of income, represented in our foreign reserves and GDP, is ultimately unsustainable.

What next?

Nepal enjoys the remittance money sent by its citizens. Approximately 3.5 million Nepalese (14% of the total population) are feeding the Nepalese government with remittances, alongside their families. This has created a fragile economy that is thriving on migrant jobs rather than internal efficiency and productivity.

As mentioned earlier, Nepal’s extremely high dependency keeps the economy in jeopardy, as migration or remittances could be impacted or frozen altogether at any time. Any vulnerability or shock to job markets in foreign countries, especially the Gulf or Malaysia, can impact a substantial amount of Nepal’s foreign assets reserve. In such a case, Nepal won’t be able to keep spending unsustainably on imports, and maintaining the pegged value of NPR could prove difficult with an unbalanced foreign asset reserve. It’s equally crucial to reduce the GDP’s 26% dependency on migrant Nepalese and their income. For this, Nepal needs to transition from a consumption-based economy and at least produce enough to keep its stability in the international trade market.

In the long run, Nepal must aim to provide satisfactory employment opportunities within the nation. Nepal has multiple ongoing hydropower projects; if construction and industrialization happen without external interference and in an efficient way, the industry might help Nepal export electricity sustainably. Similarly, the tourism sector can become a substantial source of foreign income if developed strategically. Promotion of eco-tourism, improvement of facilities and tourist infrastructures, and ensuring political stability and tourist safety can boost small businesses, hotels, and economies in major tourist destinations. Additionally, investing in industrial zones, factories, agricultural industries, and agro-processing industries could be some possible choices, which can improve our exports and increase employment. However, these projects cost a lot of money and resources, thus making them executable but in the long run, over multiple years.

In the short run, our current interim government and the to-be elected government must incentivise domestic industries and business firms. Tax reliefs, low-interest loans, and subsidies could be provided to small-scale manufacturing and agriculture-based industries. It is crucial for the diversification and strengthening of industries and businesses, as a high percentage of our GDP depends on consumption-based firms and economies.

The recent protests and uncertain political scenarios have already cut Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) and business confidence. It is equally critical for the government to ensure a stable political landscape while ensuring a sustainable and safe industrial environment, and it should be the government’s immediate priority. Nepal’s future economic strength and stability will depend on whether policymakers can transform the reliance on remittances into domestic productivity in the long run.

Works Cited

“Between the pre- and post-COVID-19, Nepal experienced the highest percentage increase in outflow of migrant workers among the Asian countries, finds out a report published jointly by ILO, ADB Institute and OECD.” International Labour Organization, 19 September 2024, https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/between-pre-and-post-covid-19-nepal-experienced-highest-percentage-increase. Accessed 10 November 2025.

The Economic Times. “What is Trade Deficit? Definition of Trade Deficit, Trade Deficit Meaning.” The Economic Times, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/definition/trade-deficit?from=mdr. Accessed 8 November 2025.

Hargrave, Marshall, and Jiwon Ma. “Understanding Foreign Exchange Reserves: Key Purposes and Global Impact.” Investopedia, 28 September 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/foreign-exchange-reserves.asp. Accessed 10 November 2025.

The Himalyan Times. “Trade deficit of approximately Rs 400 billion in three months.” Himalyan Times, Rastriya Samachar Samiti, https://thehimalayantimes.com/business/trade-deficit-of-approximately-rs-400-billion-in-three-months. Accessed 8 11 2025.

“Remittance inflow into Nepal increased 29.9 percent to Rs 177.41 billion in the first month of the current fiscal year (FY), according to the latest report of Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB).” MyRepublica Nagarik Network, https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/remittance-increases-299-percent-nepals-forex-reserves-reach-us-2003-billio-57-83.html. Accessed 10 11 2025.