Nepal’s fiscal year begins from mid-July of one year and ends around mid-July of the next year, following the Bikram Samvat Calendar. The first quarter of the fiscal year lasts from the beginning of the fiscal year, i.e, mid-July or Shrawan, till mid-October or Ashwin. Around early November, the government’s quarterly reports are officially released to the news media and announced publicly.

This fiscal quarter, unusual news has made it into headlines: Nepalese commercial banks have reported an 18.78% decrease in profits compared to FY24/25’s quarter 1 profits.

Yes, the big names such as Prabhu Bank, Rastra Banijya Bank, and Laxmi Sunrise Bank, alongside multiple others, have reported profit declines. Citizens Bank reported a loss of NPR 22.04 crores (Nepal News). This is strange, because these same banks hold around NPR 10 Kharab or NPR 1 Trillion. Their problem isn’t with not having enough money. Nepalese banks have been sitting on excess cash throughout the past three years, i.e, having a liquidity crisis. This year’s unforeseeable incidents and economic halts have only worsened their situation.

To understand how their profits, or losses, impact us, we first have to understand the idea of Liquidity.

What is Excess Liquidity?

Liquid assets are cash or assets (like gold, silver, etc.) that can be quickly exchanged into cash with minimal loss in value. In the case of Nepalese banks, they hold liquid cash, which can be easily accessed and used. While having liquid assets is especially important for financial institutions and businesses, excess liquidity, as in our case, can be a problem.

But what does the bank having excess liquidity, making a profit, or not, have anything to do with us, normal citizens?

A lot.

Excess Liquidity in Banks

Currently, the banks are holding around NPR 1 trillion. Banks don’t earn money by holding cash; they also have to lend it out responsibly.

The general population deposits their money into banks in forms of normal deposits, fixed deposits, or others. People also take loans from banks in the form of home loans, education loans, etc., and pay interest.

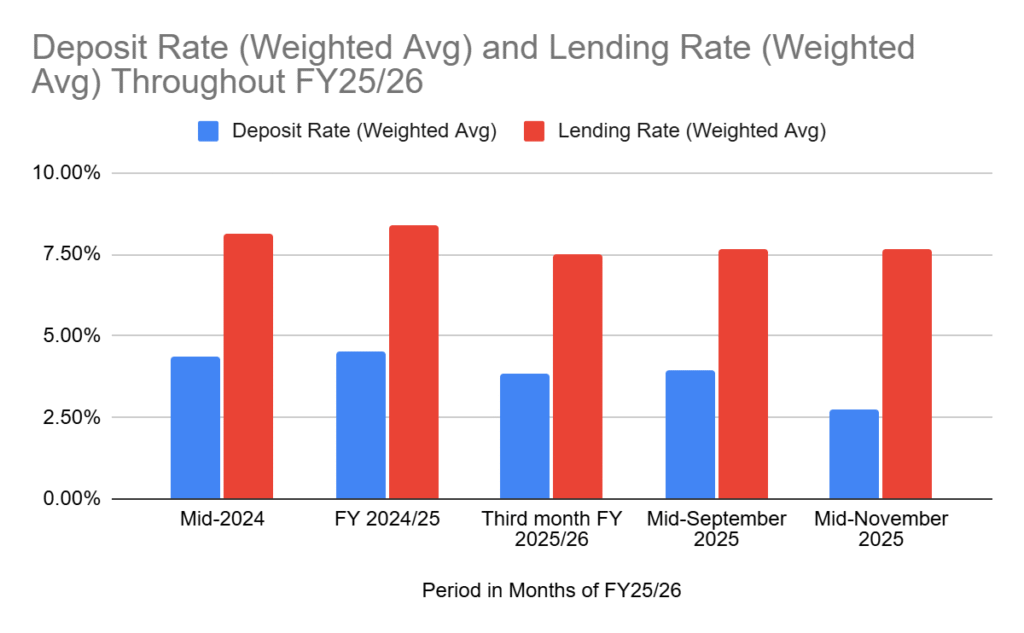

Figure 1: Banking Indicators as of 18/11/2025 (Nepal Rastra Bank)

In this case, Nepalese banks are facing a higher deposit ratio than a credit or loan ratio. From mid-October to mid-November, there were deposits of NPR 7,519 billion, while NPR 5,644 billion was lent. This can be measured by the Credit-to-Deposit or CD ratio. CD ratio measures the ratio of deposits that have been turned into credits and loans. Nepal Rastra Bank reported that this ratio is at 74.23%. This ratio suggests that almost a quarter of total deposits are sitting idle, causing the excess.

The Impacts

Banks earn through interest that loans and credit borrowers pay. A small proportion of this interest is given to depositors, while Banks keep the rest. However, the high liquidity problem has kept banks in a liquidity trap. With high negative pressures on profits, they furthermore face a larger problem of the excess idle money, which the NRB instructed to credit out. To do this, Banks have taken a step to simply decrease interest rates.

Why Lower Interest Rates?

In the current scenario of the Nepalese economy, there is lower confidence among businesses and investors, primarily attributed to the September 8 and 9 protests. Additionally, hundreds of NGOs and INGOs throughout Nepal have shut down due to USAID’s withdrawal in early February of 2025. Because of this, among other factors, a significant amount of investments in businesses and projects has paused. This has caused a slowdown in investments throughout the country. The slump of investments also means that factories, businesses, and organizations don’t have the confidence to take loans, and pause activities such as new branch openings, hiring workers, expanding factories, etc.

This has created a cycle effect. People who would normally access credit in the form of home loans, business loans, or education loans are uncertain due to the current uncertain situation of the economy. This has caused the circular flow of income in the Nepalese economy to become irregular and uncertain.

Figure 2: Bar-graph showing the change in deposit rates (weighted) and lending rates (weighted) throughout FY25/26.

As a desperate measure, Banks have decided to lower interest rates and encourage people to borrow. This is just like shops providing discounts to attract more people. With this, interest rates have dropped to their lowest levels in nearly 51 months.

Figure 3: Short interest Rates at a weighted average, Nepal Rastra Bank

Currently, interest rates on deposits are at a weighted average of 2.75% per annum in the majority of Nepal. On the other hand, average loan interest rates have decreased from ~9.33% of FY24/25 to ~7.66% as of the third month of FY25/26.

Although the rates have lowered, businesses aren’t yet operating at their full capacity, and the market hasn’t recovered meaningfully. With low levels of business, investor, and even consumer confidence, despite low interest rates, borrowers are hesitant and uncertain to take new loans despite lower interest rates. On the other hand, the Credit Information Bureau (CIB) of Nepal has already blacklisted around 150,000 borrowers out of around 1,800,000, making it difficult for banks to trust high-credit lenders.

While banks are trying to attract more lenders, those who plan to deposit money in banks for interest face a new dilemma due to the extremely low deposit interest rates. The banks are using low interest rates to signal and discourage people from making large deposits and add to their already existing excess liquidity, whilst trying to increase lending and make credit accessible.

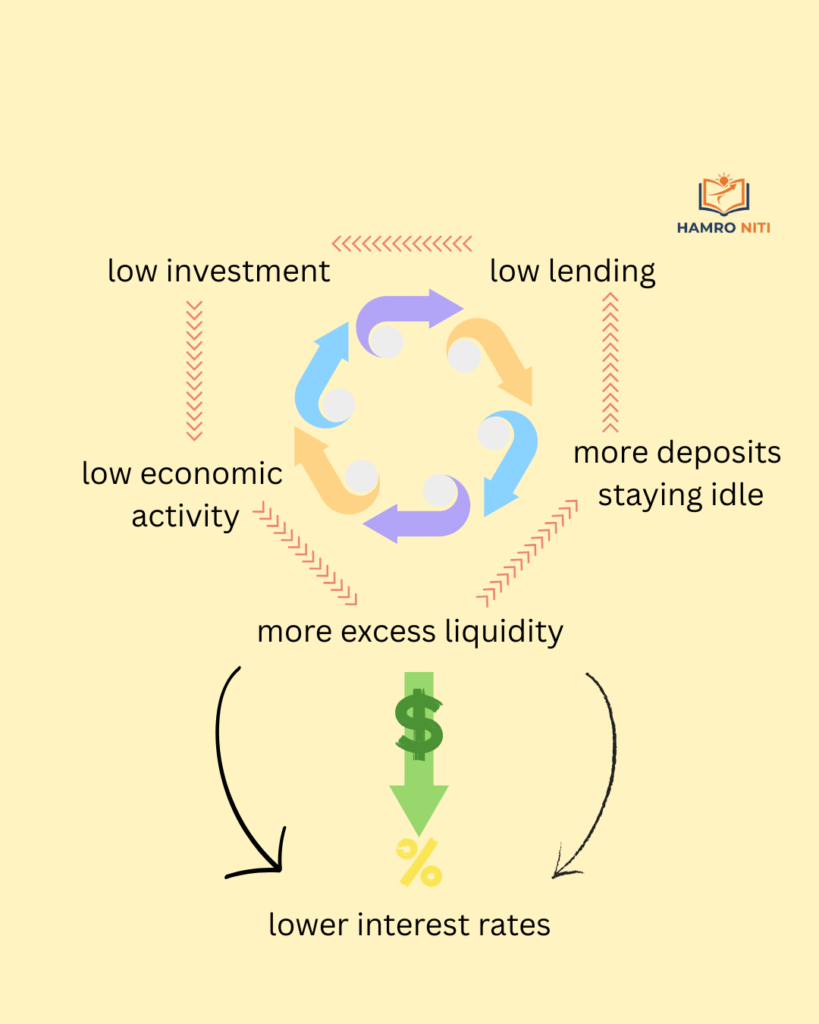

In Summary: The Circular Economy

The following image represents the current ongoing vicious cycle in the Nepalese economy, particularly in the banking and investment sector.

Figure 4: A circular economy of the banking sector in the current scenario of excess liquidity in Nepal

Banks have an excess of NPR 1 trillion, which they are willing to lend at historically low interest rates, yet borrowers and lenders are hesitant. With borrowing and credit becoming uncertain, businesses are unable to expand, invest in projects, or hire staff and human resources.

Lower investments impact the entire economy, reducing economic activity. Nepal already produces fewer goods and products, with lower investments; this number decreases further. Additionally, jobs are scarce in the market, including both low-skilled and highly skilled jobs.

Slumping of economic activity results in businesses, factories, and entrepreneurs being cautious, depositing money but not taking loans and credits. Therefore, banks again hold the excess liquid funds, perpetuating this economic cycle.

This cycle has been ongoing in our economy since 2022, and each year, it has only worsened.

This time around, the NRB has strategically cut interest rates to historically low rates in an attempt to escape this vicious cycle. Although it comes with its own potential side effects, such as possible inflation, it is a necessary and textbook step to encourage borrowers and ease access to credit. The NRB has also been absorbing the high liquidity buildup by withdrawing excess cash from the market. Currently, NRB is removing money from the economy for 84 days and even 175 days at a time. This indicates that the liquidity pressure will remain almost throughout this fiscal year, and it is a long-term goal of the bank to ease this pressure buildup.

In the second week of November, NRB absorbed NPR 50 billion for 84 days, which really demonstrates the severity of this problem.

While the Rastra Bank has taken multiple crucial and textbook steps, the current levels of business and consumer confidence are still at an all-time low. The early elections come with increased uncertainty, economic and opportunity costs. Investments have been reduced, and a credit growth and efficient money flow can only be expected after the elections in February. It is only possible to mobilize the idle funds and convert them into loans if the uncertain economic situation improves. However, this is a long-term goal for the government. Till then, the NRB must articulate efficient ways and make important changes in the banking structure of Nepal, and try to ease the pressure of existing excess liquidity.