This article explores the economic hopes, infrastructure hurdles, and environmental risks behind Nepal’s permit-free peaks policy.

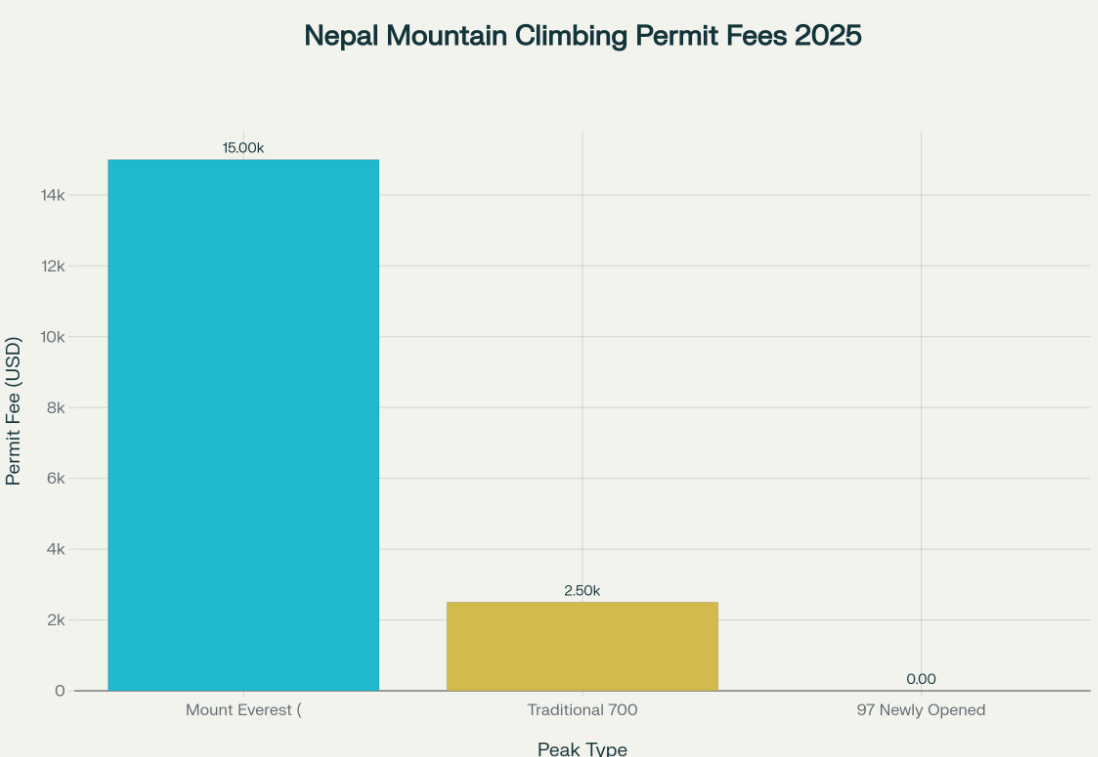

While Nepal government hiked Everest’s climbing fee from $11,000 to $15,000 in January 2025, with the new rates going into effect on September 1, 2025, the government also simultaneously waived permit fees on 97 remote peaks in Karnali and Sudurpaschim, raising a bigger question: what is the real aim of this policy, and what could it mean for tourism, and the future of Nepal’s least-visited regions?

Comparison of mountain climbing permit fees in Nepal showing the stark difference between premium Everest permits and the newly waived fees for 97 remote peaks

The Policy: What’s Happening?

On July 17, 2025, Nepal’s cabinet approved a historic move: for the next two years, climbers won’t pay any government permit fees to attempt 97(77 in karnali province & 20 in sudarpaschim province) Himalayan peaks. These mountains, ranging from 5,870 to 7,132 meters, lie scattered across the remote and rugged Karnali and Sudurpaschim provinces in Nepal’s far west. With famous summits like Api (7,132m), Saipal (7,030m), and Api West (7,076m) included, the decision marks the country’s most ambitious attempt yet to decentralize adventure tourism and spread its economic benefits to regions usually overlooked by climbing expeditions.

The policy was announced by Tourism Minister Badri Prasad Pandey, with crucial support from the Nepal Mountaineering Association and the Department of Tourism. Speaking after the decision, Dr. Narayan Prasad Regmi, Director General of the Department of Tourism, emphasized how most of these scenic mountains remain “almost untouched” due to poor accessibility and lack of infrastructure.

Map of Nepal highlighting the western provinces where 97 permit-free peaks are located.

Why Now? The Economic Logic

For decades, mountaineering in Nepal has revolved around Everest and a handful of other famous peaks in the east. In 2024, Everest alone generated 77% of all climbing permit revenue – about Rs 790 million. By contrast, the far-west attracted only 68 climbers in the past two years combined which generated only Rs 1.4 million from these climbers.

By removing permit fees for these 97 peaks, the government hopes to redirect global climbers towards Nepal’s “unexplored gems” of karnali and sudarpaschim. The policy is as much about redistribution as tourism: these provinces are among Nepal’s poorest, where outmigration, unemployment, and weak development keep local economies fragile. If even a fraction of guiding jobs, homestay income, and trekking spending moves westward, the policy could spread mountaineering’s wealth far beyond Everest’s shadow and could become a tool for local empowerment.

The Reality on the Ground

But free permits don’t mean free climbing. The Karnali province is the largest in Nepal but also the poorest, with the lowest road density in the country. The Karnali Highway, under construction for 26 years, remains largely unpaved. Reaching many peaks still requires days of walking from the nearest road or airstrip. Lodges are scarce, rescue posts almost nonexistent, and communication unreliable.

The provincial government has set aside Rs 33.72 billion for roads, water, and transport, and plans to connect all district headquarters and 19 local centers. But progress has been slow, and emergency services remain incomplete. For climbers: logistics, guides, and transport remain costly. For locals, tourism promises new income – but without training or support, it can also create pressure on fragile communities already short of services. And unless these gaps are addressed, the idea of opening “virgin peaks” may remain more symbolic than real.

The Policy Trade-offs: Environment and Equity

Every big policy comes with risks. On Everest, climbers generates 4.6 tons of waste daily during peak season. Karnali’s mountains, more ecologically fragile and less prepared, could face similar problems without proper waste systems or visitor rules.

There’s also the question of who benefits. A previous fee waiver from 2008 to 2018 attracted only modest numbers, and much of the profit went to Kathmandu-based operators rather than local households. Without certified guides, homestays, and cooperatives, communities risk being bypassed again–left to deal with litter and accidents while outsiders take the rewards.

What Will Make This Policy Work

Fee waivers are the spark, not the solution. For the policy to deliver, four pieces must fall into place:

Infrastructure: Better road links, communication towers, and rescue posts–modeled on Manang or Pheriche are essential.

Community Ownership: Training villagers as guides, porters, and homestay managers keeps income in the region and builds local buy-in.

Environmental Safeguards: A waste-deposit system, and community-led monitoring can prevent Karnali from repeating Everest’s mistakes.

Promotion: Digital campaigns, and partnerships with climbing federations are needed to bring the first wave of climbers west.

The Bottom Line

This policy is less about free climbs and more about whether Nepal can turn tourism into a shared opportunity for its most remote regions.

The test over the next two years is simple: can smart policy redirect climbers from Everest to Karnali, and can fragile mountain communities turn that interest into lasting progress?

The Nepal government is betting that the answer is yes. But the mountains, as always, will be the judge.

Comment your thoughts on this new policy.

🖋️ Saksham Ghimire