One of the most talked-about campaigns in Nepal in recent years has been Beti Padhau Beti Bachau (BPBB), meaning “Educate daughters, save daughters.” Launched in 2019, the BPBB program aimed to increase girls’ access to education by providing transport.

Discriminatory gender norms in parts of Nepal continue to negatively impact the lives of girls and women. Girls are dropping out of school, entering early marriages, and facing gender-based violence (GBV). To respond to these challenges, Province 2 launched the Beti Padhau Beti Bachau (BPBB) program, a girls-focused social protection initiative. The program aimed to reduce school dropout rates, delay early marriages, and promote gender equality by helping girls travel long distances to school. In 2019, the Province 2 government began distributing bicycles to schoolgirls under the campaign, allocating Rs 393.5 million for the fiscal year 2019-20. The program included seven components: bicycles, insurance schemes, sanitary pads, scholarships, girl-friendly toilets, and public service preparation classes.

Bicycle Distribution as a Mechanism for Empowerment

A key component of BPBB was bicycle distribution. It was designed to prevent girls from dropping out as they moved from primary to secondary school, when distances to school often increase. In this context, bicycles were framed as a practical support mechanism, but also as a symbol of empowerment that could enable independent travel.

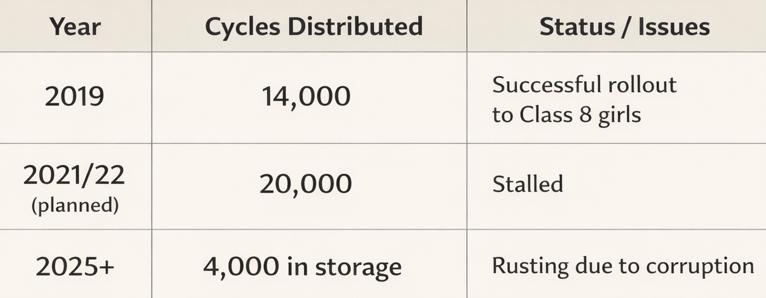

By 2019, 14,000 bicycles had reached Class 8 girls across 241 schools, with plans to distribute 20,000 more in 2021/22 (077/078). Schools and distribution sites were identified using data from the Provincial Education Directorate, while the Chief Minister’s Office (CMO) handled the rollout. Early results appeared promising. The campaign gained significant media attention, increased school attendance, and enabled some girls to travel independently to urban areas, which expanded mobility and confidence.

Systemic Failures: Corruption and Logistical Deficiencies

Despite early momentum, recent reports reveal that thousands of bicycles purchased for the campaign are rusting in storage due to corruption scandals and poor management. The Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) has charged bureaucrats in Madhesh Province with embezzling more than 50% of the provincial BPBB budget of about Rs 103.3 million. While 14,000 bicycles were distributed in 2019 across 241 schools, 4,000 more remain in storage due to the lack of a rollout plan.

The problems went beyond stalled distribution. There was no training or funding for bicycle maintenance, and no plan for the long-term lifespan of the bicycles. The absence of dedicated staff further weakened implementation. By late 2019, the campaign stalled due to the lack of local-level employees, which halted insurance schemes and distributions until mid-2020.

Even where bicycles initially improved access, discriminatory norms remained largely unchanged. The program did not develop scalable monitoring systems to track dropout reduction or delays in early marriage. Budget execution remained low, and reports up to 2025 suggest only piecemeal insurance uptake, with no comprehensive revival of the overall initiative. External partnerships, including UNESCO dialogues, highlighted ongoing challenges but did not resolve the deeper systemic problems. Ultimately, BPBB became a case study of how corruption and administrative weaknesses can waste resources and damage public trust.

Policy Recommendations for Future Initiatives

The BPBB campaign highlights major implementation gaps. While it recognized visible symptoms of gender inequality, it did not build a resilient system that could withstand corruption risks and administrative failures.

For future projects, the government should decentralize implementation by using local municipal offices for bicycle distribution. It should ensure transparency in maintenance funds and their usage, alongside training, monitoring, and evaluation to keep bicycles functional and track impact over time. Without these delivery foundations, well-intentioned social protection programs can lose momentum and leave girls with promises that do not translate into lasting change.